There is little denying that the Cascadian flag does a great job of representing the characteristics and beauty of our illahee and home. Just as its use serves to better represent place and decolonize our identity, the use of native place names helps us better understand the culture and environment that we live in. One of the defining characteristics of our bioregion is the beautiful Cascade range of volcanos running from north of Vancouver in B.C. well into California. These mountains, had names, and a history, long before the explorers of the 18th century erroneously re-titled them, most often celebrating colonists (many of questionable character) who’d never been here or had any relationship with the great peaks.

The first in a series of 12 posters featuring the native name for volcanos and features of the Cascade range.

In contrast, the native names for the mountains tell an engaging story, where the Cascade range becomes a community of dynamic and interconnected characters as they feature in myths and legends explaining how the land was formed and the millennia long relationship people have had with it. Many of the peaks have multiple names, a reality reflected by the diversity of languages present across Cascadia, and relativity with which the mountains are viewed from across the region.

In this multi post series, we recognize the native names of the volcanoes of Cascadia Illahee as we celebrate the cultures that have been existent here for thousands of years and the impact their stories have on us all.

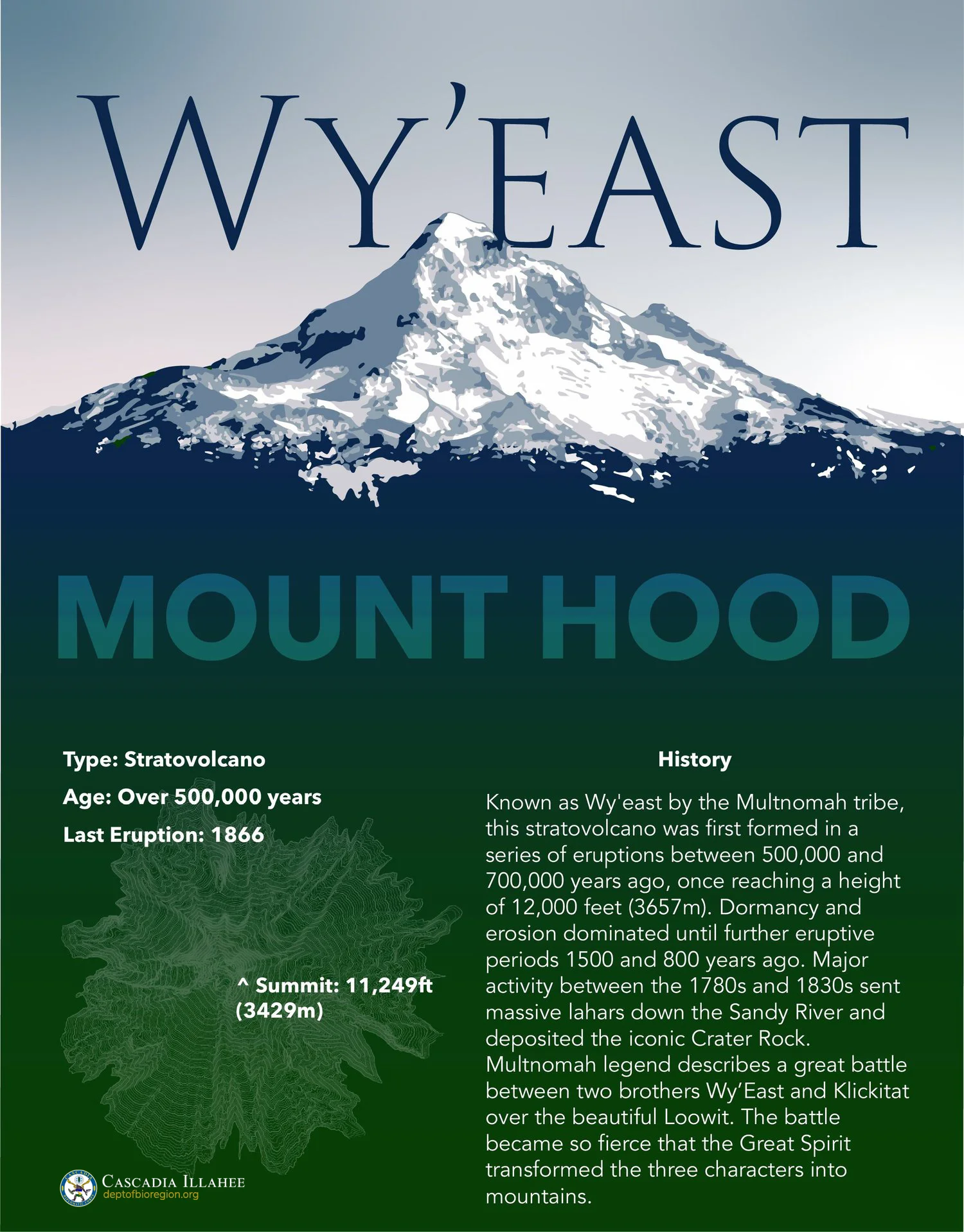

We begin with Wy’East, the native name for Mount Hood. The name originated with the Multnomah tribe of the Columbia river valley. The Great Spirit Sahalie had two sons who who began to quarrel as they aged. They grew greedy and jealous as they each wanted more than the other. One night after a great quarrel, Sahalie awoke both sons and took them to a new land. He instructed each to shoot an arrow to opposite sides of a large river, instructing them that where his arrow landed would become his country and he would become chief.

One shot his arrow into the Willamette Valley, and became the father of the Multnomah tribe, while the other brother shot his arrow north of the river, becoming the father of the Klickitat tribe. Sahalie then told the brothers he would build a bridge as a symbol of peace to link the two tribes. So long as they remained friendly the bridge of Tahmahnawis would remain.

Many years passed in peace as the two peoples crossed the bridge in friendship and traded with one another. There was no hunger and everyone was warm. As time passed, the greed, jealousy and wickedness crept into the people, and the two tribes fought. Sahalie again was displeased, and punished the people by taking away the sun and their fires. Rains came, and the people grew cold and hungry. They begged the great spirit for fire and and recognized their flaws.

Sahalie found an old woman who had remained above the battles of the people and had fire still. He asked her if she would go to the bridge with her fire and keep it burning there forever as a symbol of his greatness. He told her the people would see it, and to encourage them to get some for themselves. The great spirit said he would grant her one wish for completing this task. Her name was Loo-wit, and she wished to become young and beautiful again.

The next morning, a young and beautiful woman with a fire appeared next to the bridge. People from both sides of the river came and gathered some taking it back to their homes and restoring warmth and peace to their communities. In time Loo-wit met two handsome your men. One from the south bank of the river was a young Chief named Wy’East. The other, who came from the north bank was Chief Kilickitat. Loo-wit was captivated by them both, and could not choose who she loved more. The two Chiefs grew jealous and again battles between the brothers, made chiefs began.

Tired of the foolishness of his two sons, Sahalie separated the brothers and turned them into mountains one forever south of the river still known as Wy’east (Mount Hood) and the other, Klickitat (Mount Adams) to the north, his head bowed towards a mountain to the west. That mountain is what became of the woman the brothers both loved Loo-wit (Mount Saint Helens). Occasionally the two brothers, immortalized in their anger, throw stones and fire at one another. This is why the point between them on the river has narrows known as the Dalles.

This foundation story illustrates how the relationship of the Multnomah tribe to the three peaks they could see from their land formed not only mythical characters in a story, but geological explanations for the placement of the mountains, the character of the peaks, and an explanation for their eruptions. Indigenous people found elsewhere in relationship to the mountains had different stories and names for the mountains that represent a distinct and local perspective on the volcanoes to that place. The use of these native names better represents the life that we all share with the nature around us, and instead of the common names which celebrate forgotten and foreign characters of a colonial era, shifts the focus back to the abundant and thriving nature of Cascadia.