Landback, Nature Sovereignty & How it Relates to Cascadia: A Settler FAQ

Non-Indigenous people have a lot of questions about the Land Back movement: What does it mean? Who will the land be given back to? How will it be governed? Do people want to force “settlers” to leave the continent? In this article we clear up some common questions, misconceptions about the landback movement.

Why does Cascadia and land back need to happen? Why doesn’t the land rightfully belong to the united states and canada?

The United States and Canada are foundationally broken systems.

When Indigenous Nations entered into treaties with the United States and Britain, they never intended to transfer ownership as it is know thought of by the United States and Canada. There was never the legal consideration from Indigenous Nations (i.e., a land transfer offer) required for the land to be given, and in many cases treaties were signed under extreme duress, including enslavement, starvation, torture and genocide. Terms we now equate with war crimes and crimes against humanity. Treaties allowed settlers to occupy lands, and both sides promised to work in harmony and to be peaceful with one another, but colonizer states have often used violence, broken the terms of the agreements, and in some cases still occupy unceded lands. Relying on “Manifest Destiny”, that the land was “unclaimed”, “unused” or “undiscovered”, the hundreds of nations still occupying our continent were ignored, and new colonists created the legal fiction that the land could be “owned”, and that the constitution granted the right to such “unclaimed” territory. For hundreds of years indigenous, black, immigrant populations and women were disenfranchised from participating in this system, while populations, cultural traditions were exterminated.

Even today, the US constitution forces itself, and it’s subdivision of territory as private property into smaller and smaller parcels as the “supreme law of the land”, and does not allow for “tribal nations” to exist as anything but "domestic dependent nations". Never can they exist as anything more than that, or have true independence, self governance or sovereignty. In Canada, the government routinely ignores the conditions laid out in existing and modern treaties, and still claims sovereignty over, and exploits resources from unceded lands actively being lived on and used by First Nation people.

Land Back and Cascadia needs to happen so all other aspects of Indigenous livelihood can return with it, and that we can build a system for all of us living here, that starts will of us living here included. Land Back means nourishing our relationship to all things on the land, but it would also mean getting back in touch with languages, traditional familial and governing systems, and creating a better relationship with healing and medicine. Only when all of us are at the table, in an equal way, can we begin to have that conversation of what it looks like.

Examples of these types of shared stewardship can be found in systems like that of the Maori and New Zealand, which are continuing to develop tools of shared governance, stewardship, and approval processes that use aboriginal principles and standards for decision making.

What about lands where the Indigenous territory spans colonial borders, like provinces or the U.S. border? How would you approach those?

Borders are a colonial construct. The land and people living here preceded the creation of borders, and these arbitrary borders must be dismantled. Any border was imposed unilaterally, without consulting the Indigenous Nations that would be impacted. Resolving these issues is not difficult. Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous Nations must be included from the bottom up, in discussions about interprovincial borders, and the shared management of resources within those borders. Between Canada and the U.S., any person of Aboriginal descent should have free passage over the the US/Canadian and US/Mexican border. Cascadian institutions need to break down the idea that Indigenous Nations are bound by any one country.

From the start, we must entirely rethink our conception and framework for what nations, communities and borders can be. Rivers are borders. Mountains are borders. How birds migrate, animals roam, fires burn, food grows, water flows are all borders that matter quite a lot. How can we envision bioregional administrative frameworks based on overlapping needs and use based on systems of abundance and co-operation, rather than scarcity and privatization, as best determined by those most impacted? What can we learn from place appropriate technologies and ways of living that have been practiced for thousands of years? Cascadia and bioregions are important because we must rethink our relationship to the places where we live. Rather than citizens of arbitrary nation states and lines drawn on maps by people who have never set foot there, we must become citizens and stewards of our watersheds. Names don’t matter, but where we live does. Where we are born or from doesn’t matter too much, but where we are living now, and how we are living are important.

What does Landback mean in a global sense?

Even if the United States and Canada continue to ignore Indigenous sovereignties, decolonization is the future. The Cascadia bioregion was one of the last places settled by colonizers in North America and around the world hundreds of new peoples have regained acknowledgement of their sovereignty and personhood through the United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Rights. The US and Canada are no different. But even the term “United Nations” and “international” must be examined, as it uses the context of the nation state, and the colonizer as it’s default.

Does land back mean exclusion of people from colonial descent?

No. While this is an incredibly complex issue, involving generations of trauma, cultural erasure and displacement, we cannot and should not support ethno-states, no matter the intention, it is clear in the world the harm that can come from including some, while excluding others based on birth, nationality or race. Instead we must strive for systems of reparations, truth, reconciliation, and making sure there is real means for cultural expression, inclusion and governance.

However, while displacement and erasure are not core values of the Land Back movement; violent, extractive and capitalistic goals and practices are not welcome.

In the case of many US and Canadian Indigenous Nations, the Bureau of Indian Management has ruled Native Nations as puppet states, degraded the quality of life to a third world nation and created systems of abject poverty, and when expedient abolished Indigenous Sovereignties with the swipe of a pen. Blood lines have been used a tool to divide and deny benefits for tribal members and exclude benefits, rather than include them. While the choice should be one made by each Indigenous Nations as they choose - time and time again, when given the chance, Indigenous Nations choose to govern in manners which include everyone, for the benefit of all inhabitants and the land itself, from a generational approach, rather than only humans or some particular subset of human. Together, we must fundamentally rethink and challenge the notion of citizenship assigned by birth itself.

What are some good examples of Land Back?

One of best examples of Land Back in North America is the Yukon Land Claims, which included negotiating and settling Indigenous land claims between First Nations and the Canadian government. Based on historic occupancy and use, First Nations claim basic rights to all the lands they occupy. These nations never signed any treaties, and the lands were unceded even though Canada claimed sovereignty over them. Chief Jim Boss of the Ta'an Kwach'an had requested compensation from the Canadian government for lost lands and hunting grounds as a result of the Klondike Gold Rush as early as 1902, which was promptly ignored. It was not until the 1973 that the issue was raised again in 1973 with the publication of Together Today For our Children Tomorrow by Chief Elijah Smith. Negotiations took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s, culminating in an agreement which was ultimately rejected.

Negotiations resumed in the late 1980s and culminated to the "Umbrella Final Agreement" (UFA) in 1990. The UFA is used as the framework or template for individual agreements with each of the fourteen Yukon First Nations recognized by the federal government. It was signed in 1993 and the first four First Nations ratified their land claims agreements in 1995. To date (January, 2016), eleven of the fourteen First Nations have signed and ratified an agreement. Presently, White River First Nation, Liard First Nation and Ross River Dena Council are not negotiating. They remain Indian Bands under the federal Indian Act.[2]

Unlike most other Canadian land claims agreements that apply only to Status Indians, the Yukon First Nations insisted that the agreements involve everyone they considered part of their nation, whether they were recognized as Status Indians or not under federal government rules. In 1973, the Yukon Indian Brotherhood and the Yukon Association of Non-Status Indians formed the Council for Yukon Indians (CYI) to negotiate a land claims agreement. The two organizations and the Council formally merged in 1980 under the name of Council for Yukon Indians. In 1995, CYI was renamed to the Council of Yukon First Nations.

The Yukon Land Claims refer to the process of negotiating and settling Indigenous land claim agreements in Yukon, Canada between First Nations and the federal government. Based on historic occupancy and use, the First Nations claim basic rights to all the lands

if you look at MTAs, particularly more recent ones like the Yukon Umbrella Final Agreement, signed in 1993, you will see there is language about including Indigenous Peoples in decision-making over the land, waters, and resources in those Nations’ traditional territories. This kind of relationship between Indigenous Nations and Canadians is one of the closest Land Back situations we have gotten to date. However, Canada still breaks these agreements at a similar rate as the other treaties made over the past 300 years (see the Supreme Court decision Nacho Nyak Dun v. Yukon).

Elwah Dam Removal

Maori Shared Governance framework

How do I support this movement if I don’t have land? I rent an apartment from a landlord.

Stop using the term “Pacific Northwest”

Use indigenous languages. Share local histories and contexts. Petition to rename streets, mountains, rivers, and landmarks.

Petition your government and call your elected representatives and ask for Canada to honour the treaties. Demand the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples at the table to make decisions alongside the (mostly) non-Indigenous governments that make decisions over our lands, waters, and resources.

Advocate for defunding the police in urban centres. Work toward municipal goals that centre the needs of Indigenous communities, including affordable living, access to mental health resources, harm reduction, and livable wages. Everyone is better situated to work toward Land Back when their basic needs are being met.

As part of this bioregion and our home, the Cascadia Bioregional Party recognize that we live on the ceded and unceded lands of generations of First Nation, Aboriginal and Indigenous people who have lived here since time immemorial. We recognize that we exist today on the backs of generational trauma, genocide, racism, forced removal, land seizure, cultural erasure, exploitation the systemic and personal results still exist with us here actively today. As nation states built from these horrendous acts, and built to enshrine the rights of dividing and subdiviving this land as property between its citizens and enforcing these systemic differences, American and Canadian citizens will never be able to undo the harm wrought before them or move away from these injustices that have been built into the very foundation of their constitutional documents while a part of these governments.

Today, the United States and Canadian governments serve as the largest forces of white supremacy and economic hegemony in the world. Through the commodification and stripping of resources, economic and cultural mono cropping, overthrowing governments that they disagree with, environmental exploitation and untamed military might, these nation states enforce a will that benefit a tiny few, while reducing the overall well being and livelihood of the many. We feel that any argument that does not immediately support the removal of, and dissolution of these power centers, and the arbitrary and colonial boundaries that they derive and support is an argument which actively supports these policies, through passivity, through tax dollars, and the benefits derived of extreme national and global injustice and exploitation.

For us, the conversation of Cascadia starts and ends with First Nations and Indigenous organizers and communities throughout the Cascadia bioregion. We are proud to have many members of First Nations as part of our organizing teams and groups, and to give space to amplify their voices and issues important to them. The Cascadia Bioregional Party actively supports decolonizing nation state borders within North America; removing ourselves from systems which are non-representative of the place, people and land; and working with all inhabitants, especially those who have been traditionally marginalized or left with out voice, to build something new.In light of these facts, the Cascadia Bioregional Party works to

Reach out with every first nation community within Cascadia to align on pathways for truth, compensation, land return where decided and other forms of reconciliation;

identify areas of solidarity and mutual aid including generational trauma,

indigenous delegates & representatives to represent their own interests

co-stewardship of ecosystem areas and greater watershed rights and protections.

co-create confederated systems of governance that we are all a part of, and all stakeholders in

support cultural revival programs that assist Indigenous Nations within Cascadia, traditional language revival, and use of indigenous place names, stories and history.

As described by Cascadia Institute director David McCloskey – Cascadia is a construct that shapes an identity and place. This region has had many similar names in the near past: New Spain, New Caledonia, New Archangel, New Georgia, the Columbia Department, the Oregon Territory, the Northwest, the Pacific Southwest, the Pacific Slope, Ecotopia, the New Pacific, Ecolopolis, each chosen to convey an idea, often imposed by a different ruler or power, often thousands of miles away with little connection other than a few lines and names on a map.

The term Pacific Northwest is largely used in the American context, while the Canadian equivalent is Canadian West. and begs the question… “Northwest of What?”. In both of these examples, the answer is the distance away from the political capitals of their respective political entities.

Cascadia Illahee then is the name of the land, given to it by the people who live here. Rather than names representing far off people or places, Cascadia highlights the importance of the water we all rely on, and the cascading cascades as the the first drop hits the ground, through evergreen forests and desert canyons, as it journeys on its way to the eastern rim of the Pacific Ocean.

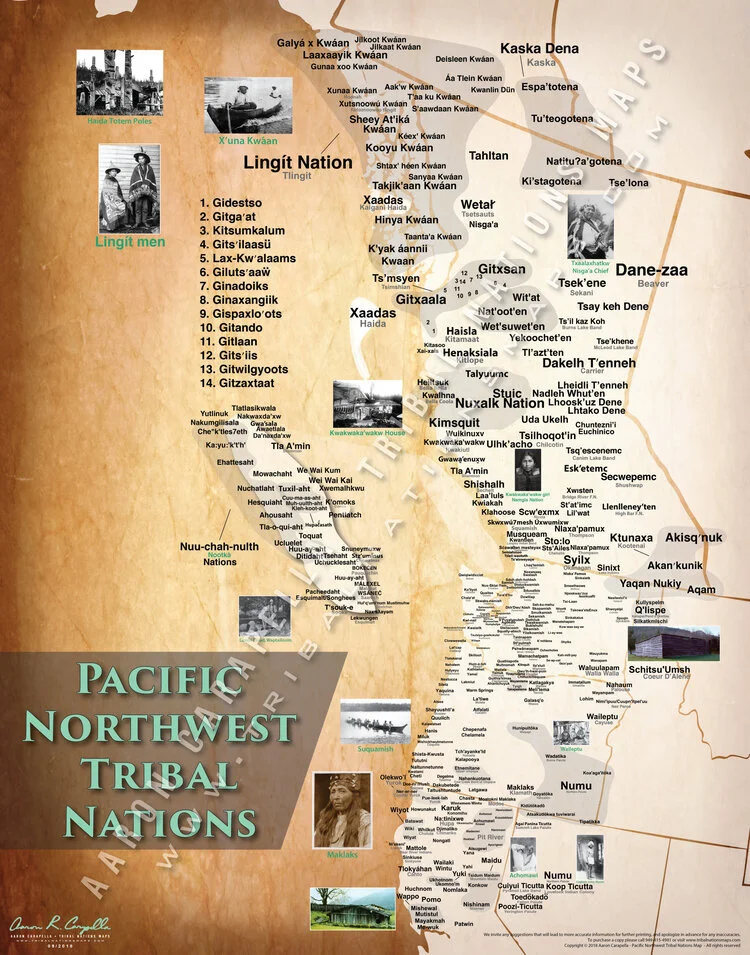

Though different linguistic maps match Cascadia very closely, first nation populations inhabited the region and had many different names for the people, cultures, places and areas, there was no one unified name for the larger area of the Cascadia bioregion in it’s entirety. Before 1800, it is estimated that more than 500,000 people lived within the region in dozens of tribes such as the Chinook, Haida, Nootka and Tlingit.

The people of these nations share a common understanding that their very existence depends on the respectful enjoyment of the regions river basins vast land and water resources. They believe their very souls and spirits were and are inextricably tied to the natural world and all its inhabitants. Among those inhabitants, none are more important than the millions of salmon that bring sustenance and prosperity to the region’s rivers and streams. Indian fishers have fished the waters of the Columbia Basin for thousands of years. It was a central part of their cultures, societies, and religions.

For us, the conversation of Cascadia starts and ends with First Nations and Indigenous organizers and communities throughout the Cacadia bioregion. We are proud to have many members of First Nations as part of our organizing teams and groups, and to give space to amplify their voices and issues important to them.

Cascadian Coast Native cultural areas extends along the coast from southern Alaska, Washington and Oregon and down the Canadian province of British Columbia to the northern edge of California, and traded extensively with the Plateau people further inland. With the arrival of colonial explorers, traders and settlers, many of the indigenous populations were hit very hard by disease. By 1850, it is documented that smallpox wiped out roughly 65 to 95% of Northwestern Indian populations with some estimated 100,000 still remaining. Since then, many first nations people were subjected to forced removal, displacement, separation, and programs designed to eradicate native linguistic languages, tradition and culture.

We believe in the sovereignty of the nations and communities within the Cascadian bioregion, including respect for their land and territory. We seek to begin a dialogue with each First Nation as part of a process of truth and reconciliation set within an acknowledgement of past injustice, genocide within the culture, history and context of each, in a framework of global human rights to build consensus and explore pathway forwards.

We believe in a confederation with the many First Nations within the Cascadia bioregion for scalable, fluid forms of governance, representation where desired with a Cascadian government working together around common shared principles we have all worked to establish. This starts with round table discussions with each First Nation and group to explore what this future looks like and to come to agreements with each, and majority and consensus approval from all.

As part of this we support the incorporation of indigenous place names, culture, languages and history into our learning and sharing, and embrace the revitalization of Chinuk Wawa, the indigenous and pidgin trade language which was the lingua franqua pre-colonial arrival, and the most spoken second language of the region through the 1880’s.