Carrier is generally regarded as one of three members of the central British Columbia subgroup of Athabaskan, the other two being Babine-Witsuwit'en and Tŝilhqot’in. Carrier proper consists of two regional dialect groups, Dakelh (ᑕᗸᒡ) and Southern Carrier, where the latter is divided into two subgroups, Fraser/Nechakoh and Blackwater which are further subdivided into the individual dialects.

The Fraser/Nechakoh subdivision of Southern Carrier includes the Lheidli, Saik'uz, Nadleh, Nautey, Stelakoh, Stoney Creek, Prince George, and Cheslatta dialects. The Blackwater division includes the Anahim Lake, Red Bluff, Nazko, Kluskus, and Ulkatcho dialects, and is is mutually comprehensible with all other Carrier dialects.

Southern Carrier has an extremely extensive and productive system of noun classifications. It has multiple classification subsystems and they can take place in the same sentence or same verb.

The etymology of 'Carrier'

The name 'Carrier' is a translation of the Sekani name 'aghele' meaning “people who carry things around on their backs", due to the fact that the first Europeans to learn of the Carrier, the Northwest Company explorers led by Alexander Mackenzie, first passed through the territory of the Carriers' Sekani neighbors. The received view of the origin of the Sekani name is that it refers to the distinctive Carrier mortuary practice in which a widow carried her husband's ashes on her back during the period of mourning. An alternative hypothesis is that it refers to the fact that the Dakelh, unlike the Sekani, participated in trade with the coast, which required packing loads of goods over the Grease Trails (also known as the “Alexander Mackenzie Heritage Trail”).

Writing system

Carrier was formerly written in the Carrier syllabary, or Déné Syllabics, which was devised by missionary and linguist Adrien-Gabriel Morice in 1885. He adapted it from the syllabic writing systems developed for the Athabaskan languages of the Northwest Territories of Canada by Emile Petitot, and from the Cree Syllabics developed by James Evans.

A good deal of scholarly material, together with the first edition of the 'Little Catechism' and the third edition of a 'Prayerbook', is written in the writing system used by the missionary priest Adrien-Gabriel Morice in his scholarly work. This writing system was a somewhat idiosyncratic version of the phonetic transcription of the time. It is subphonemic and was never used by Carrier people themselves, though many learned to read the Prayerbook in it.

The Carrier syllabary was widely used for several decades for such purposes as writing diaries and letters and leaving messages on trees, but began to fade from use in the 1930s. Though the syllabary is no longer used or understood by many people, there has been a recent revival of interest in it and it occasionally appears on plaques and memorials.

In the 1960s, the Carrier Linguistic Committee in Fort St James developed an alternative writing system based on the Latin alphabet, designed to be typed on a standard English typewriter.

It uses numerous digraphs and trigraphs to write the many Carrier consonants not found in English, e.g. ⟨gh⟩ for [ɣ] and ⟨lh⟩ for [ɬ], with an apostrophe to mark glottalization, e.g. ⟨ts'⟩ for the ejective alveolar affricate. Letters generally have their English rather than European values. For example, ⟨u⟩ represents /ə/ while ⟨oo⟩ represents /u/. The only diacritic it uses in its standard form is the underscore, which is written under the sibilants (⟨s̠⟩, ⟨z̠⟩, ⟨t̠s̠⟩, and ⟨d̠z̠⟩) to indicate that the consonant is laminal denti-alveolar rather than apical alveolar. An acute accent is sometimes used to mark high tone, but tone is not routinely written in Dakelh.

Currently, the Latin-inspired CLC script is the most commonly used writing system for Dakelh.

Syntax

In general terms, Carrier is a head-final language: the verb comes at the end of the clause, adpositions are postpositions rather than prepositions, and complementizers follow their clause. However, it is not consistently head-final: in head-external relative clauses, the relative clause follows the head noun. Carrier has both head-internal and head-external relative clauses. The subject usually precedes the object if one is present.

Carrier is an 'everything-drop' language. A verb can form a grammatical sentence by itself. It is not in general necessary for the subject or object to be expressed overtly by a noun phrase or pronoun.

Contact with other languages

Dakelh is neighbored on the west by Babine-Witsuwit'en and Haisla, to the north by Sekani, to the southeast by Shuswap, to the south by Chilcotin, and to the southwest by Nuxalk. Furthermore, in the past few centuries, with the westward movement of the Plains Cree, there has been contact with the Cree from the East. Dakelh has borrowed from some of these languages, but apparently not in large numbers. Loans from Cree include [məsdus] ('cow') from Cree (which originally meant "buffalo" but extended to "cow" already in Cree) and [sunija] ('money, precious metal'). There are also loans from languages that do not directly neighbor Dakelh territory. A particularly interesting example is [maj] ('berry, fruit'), a loan from Gitksan, which has been borrowed into all Dakelh dialects and has displaced the original Athabascan word.

European contact has brought loans from a number of sources. The majority of demonstrable loans into Dakelh are from French, though it is not generally clear whether they come directly from French or via Chinook Jargon. Loans from French include [liɡok] ('chicken') (from French le coq 'rooster'), [lisel] (from le sel 'salt'), and [lizas] ('angel'). As these examples show, the French article is normally incorporated into the Dakelh borrowing. A single loan from Spanish is known: [mandah] ('canvas, tarpaulin'), apparently acquired from Spanish-speaking packers.

The trade language Chinook Jargon came into use among Dakelh people as a result of European contact. Most Dakelh people never knew Chinook Jargon. It appears to have been known in most areas primarily by men who had spent time freighting on the Fraser River. Knowledge of Chinook Jargon may have been more common in the southwestern part of Dakelh country due to its use at Bella Coola. The southwestern dialects have more loans from Chinook Jargon than other dialects. For example, while most dialects use the Cree loan described above for "money", the southwestern dialects use [tʃikəmin], which is from Chinook Jargon. The word [daji] ('chief') is a loan from Chinook Jargon.

European contact brought many new objects and ideas. The names for some were borrowed, but in most cases terms have been created using the morphological resources of the language, or by extending or shifting the meaning of existing terms. Thus, [tɬʼuɬ] now means not only "rope" but also "wire", while [kʼa] has shifted from its original meaning of "arrow" to mean "cartridge" and [ʔəɬtih] has shifted from "bow" to "rifle". [hutʼəp], originally "leeches" now also means "pasta". A microwave oven is referred to as [ʔa benəlwəs] ('that by means of which things are warmed quickly'). "Mustard" is [tsʼudənetsan] ('children's feces'), presumably after the texture and color rather than the flavor.

Place names in Dakelh

Here are the Dakelh names for some of the major places in Dakelh territory, written in the Carrier Linguistic Committee writing system:

Sign saying "Wheni Lheidli T'enneh ts'inli" meaning “We are Lheidli T'enneh” in the Lheidli dialect.

Mount Pope – Nak'al

Fort St. James – Nakʼaz̠dli

Stuart Lake – Nakʼalbun

Stuart River – Nakʼalkoh

Fraser Lake – Nadlehbun

Nautley River – Nadlehkoh

Endako River – Ndakoh

Stellako River – Stellakoh

Tachie River – Duzdlikoh

Nechako River – Nechakoh

Fraser River – Lhtakoh

Prince George - Lheidli

Babine Lake – Nadobun

Burns Lake – T̠s̠elhkʼazkoh

Francois Lake – Nedabun

Cluculz Lake – Lhoohkʼuz

Fluent Speakers

Figures reported in 2014 stated about 680 fluent speakers of Carrier, and another 1,380 people with some knowledge of the language.

According to a 2016 census conducted by the Government of Canada, there were 1,270 fluent speakers of the Carrier language. Among the 1,270 speakers, 1,045 have the language as a single mother tongue and 225 have the language as one of their mother tongues.

Status

Like most of the languages of British Columbia, Dakelh is an endangered language. Only about 10% of Dakelh people now speak the Dakelh language, hardly any of them children. Members of the generation following that of the last speakers can often understand the language but they do not contribute to its transmission.

The UNESCO status of Carrier/Dakelh is "Severely Endangered", which means the language rates an average of 2/5 on UNESCO's 9 factors of language vitality, with 5 being safe and 0 being extinct. According to Dwyer's article on tools and techniques for endangered language assessment and revitalization, the three most critical factors out of the nine are factors numbered one - intergenerational transmission, three - proportion of speakers within the total population, and four - proportion of speakers within the total population. Carrier scores in the "severely endangered" category for all three of these most important factors, as well as most of the nine.

Revitalization and Maintenance Efforts

Carrier is taught as a second language in both public and band schools throughout the territory. This instruction provides an acquaintance with the language but has not proven effective in producing functional knowledge of the language. Carrier has also been taught at the University of Northern British Columbia, the College of New Caledonia, and the University of British Columbia. Several communities have underway mentor-apprentice programs and language nests.

The Yinka Dene Language Institute (YDLI) is charged with the maintenance and promotion of Dakelh language and culture. Its activities include research, archiving, curriculum development, teacher training, literacy instruction, and production of teaching and reference materials.

Prior to the founding of YDLI in 1988 the Carrier Linguistic Committee, a group based in Fort Saint James affiliated with the Summer Institute of Linguistics, produced a number of publications in Dakelh, literacy materials for several dialects, a 3000-entry dictionary of the Stuart Lake dialect, and various other materials.

The Carrier Linguistic Committee is largely responsible for literacy among younger speakers of the language. The Carrier Bible Translation Committee produced a translation of the New Testament that was published in 1995. An adaptation to Blackwater dialect appeared in 2002.

Documentation efforts have been varied and the extent of documentation differs considerably from dialect to dialect. By far the best-documented dialect is the Stuart Lake dialect, of which Father Adrien-Gabriel Morice published a massive grammar and dictionary. More recent work includes the publication of some substantial pieces of text by the Carrier Linguistic Committee, the publication of a grammar sketch, and the on-going creation of a large electronic dictionary, with a corresponding print version, that contains earlier material, including Morice's, as well as much new material. For other dialects, there are print and/or electronic dictionaries ranging from 1,500 or so entries up to over 9,000.

FirstVoices Language Learning

FirstVoices Website

FirstVoices is an online indigenous language archiving and learning resource administered by the First Peoples' Cultural Council of British Columbia, Canada. Dakelh/Southern Carrier language is one of the languages documented on the website. Information on alphabets, words, phrases, songs, and stories are available. Both orthography and voice recordings are provided on the website. Games and a kids portal are also available for pre-readers to engage with the language.

FirstVoices App

The Nazko-Dakelh mobile application has a bilingual dictionary and a collection of Dakelh/Southern Carrier language phrases that are archived on the FirstVoices website. It is available for free on both Apple and Android mobile operating systems.

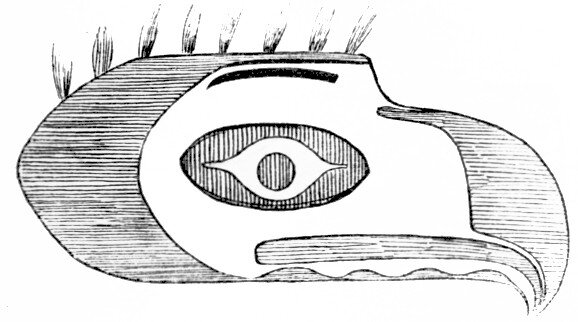

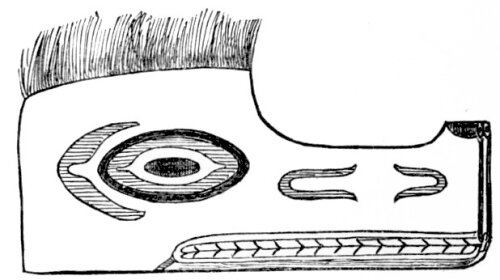

![Mask Used in the Black Tamahnous Ceremonies by the Clallams.[The markings are of different colors. The wearer sees through the nostrils.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/599f4601e3df283ad2ee5d10/1603770763763-36565220GMQXRLINDCFB/Mask+Used+in+the+Black+Tamahnous+Ceremonies+by+the+Clallams..jpg)