MESACHIE

[me-SA'-chi] — adjective

Meaning: Bad; bitter; cruel; depravity; dissolute; dung; evil; filthy; grumpy; harm; immodest; immoral; iniquity; insolence; malign; naughty; nasty; obscene; sin; sinner; treacherous; ungodly; unrighteous; unruly; unworthy; vice; vile; wicked.

Origin: Chinook, masáchi “Bad”; “wicked” < Chinook masachi "evil","nasty","malign" (Chinookan languages of Washington and Oregon)

"Mesachie" (occasionally written as “mesahchie”, mesatchee”, or “masachi”) is used in Chinook to indicate anything worse than "Cultas" (bad). While there are other words in Chinook Jargon to describe spirits or malign forces and states of being, “mesachie” has only a negative meaning, representing something bad, vile, vicious in the sense of vileness, filth, dirtiness, vice, rottenness, etc., whether in the abstract or in the concrete. It is probably more often used to describe things as being obscene or depraved than in any other sense, though it covers the whole catalogue of things or conditions that are "worse than the worst," "rotten to the core," and all like ideas where the term "bad" does not reach far enough. It also means dangerous or "danger-from" vile things. The words used before or after it qualify its meaning, or couple the vile meaning with the ordinary meaning of any other word.

It has sometimes been translated as "naughty" or "mischievous" when used to describe a child, but this does not seem to embrace the malice and innate evil implicit in the context of this term, and appears to be used hyperbole (i.e. "evil child" as a scold). Generally it is a word understood to mean "the limit of human depravity" from all angles, and can be used to mean anything from simple “mesachie mamook” (misconduct) to a “mesachie tumtum” (mean spirited, malice) effort to “mamook mesachie” (to harm, to spoil) something.

A “mesachie klootchman” (harlot) may “haul kopa mesachie” (tempt) or “mahsh mesachie kunamokst” (adulterate), while a “mesachie man” (transgressor) could also be a “delate mesachie man” (a very wicked man), who might be a “mesachie tillikum” (enemy, rascal, sinner, villain) or a “hyas mesachie tillikum” (outlaw).

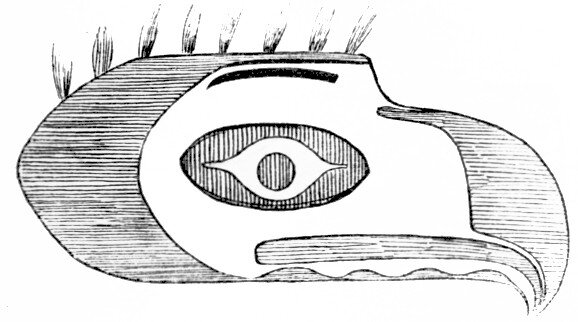

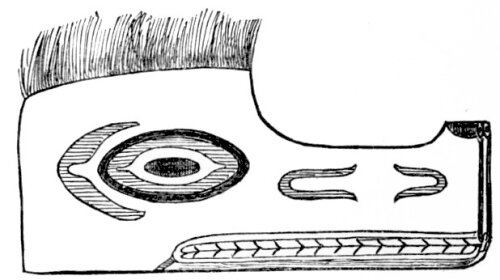

If one were to “wawa mesachie” (to curse, swear) or “mesachie wawa” (curse, slander), that might be considered one type of severity, though a “mesachie wind” (gale, storm, bad weather) could be considerably "elip mesachie” (worse), though there are things that would be classified as something "elip mesachie kopa konaway" (worse than all, worst), such as “mesachie tamahnous” (demon, fiend, witchcraft, necromancy).

Characters in a horror film will undoubtedly find themselves in "mesachie mitlite" (danger, peril, the place where bad is) in a place that is likely “hiyu mesachie mitlite” (unclean), and in a state of mind that is best described as “hyas mesachie” (horrible, horrid) or “delate hyas mesachie” (terrible, terror).

“Mesachie”, like many words in Chinook Wawa, has lent itself to many place names in Cascadia, including:

Mesachie Lake is an unincorporated community in the Cowichan Valley region of Vancouver Island, located 5 km (3.1 miles) west of the village of Lake Cowichan. Founded in 1942 by the Hillcrest Lumber Company, which built houses for its workers and their families, the community lies between the south shore of Cowichan Lake to the west, and Mesachie Lake to the east. The lumber company planted many non-native fruit and shade trees which have since been given heritage status.

Mesachie Nose is a glacial formation point in British Columbia southeast of Labouchere Point with an elevation of 31 meters (101.7 feet) that plunges straight down into the water. The water here is frequently whipped into steep chop by the wind, and when a south-western wind is blowing, the Nose is apparently a bad place to be, as an unpleasant backwash can form off its precipitous cliff.

Mesahchie Peak, located 0.25 mi 0.40 km (0.25 miles) east of Katsuk Peak at an elevation of 2,681 meters (8,795 feet), is the highest peak of Ragged Ridge, and is one of the hundred highest mountains of Washington. The pass resides in a neighborhood of rich alpine splendor, and it is the north side of the mountain which provides the most inspiring climbing. There is a North Ridge, a Northwest Ridge, and icefall on the Mesahchie Glacier and an icy couloir route which joins the East Ridge. The easiest route is the South Rib, which requires exposed class 3 climbing and some route finding skill. Both the Katsuk and Mesahchie Glaciers descended down the northwest and northeast flanks of the peak respectively.

Mesatchee Creek is a stream located near Chinook Pass, off Highway 410, east of Mount Rainier National Park. At an elevation of 694 metres (2276.9 feet) above sea level, Mesatchee Creek has cut a rather substantial canyon as it flows down the side of the well-sculpted glacial valley, creating several waterfalls along its journey. This is the final major drop, where the creek skips down a jagged face and into a rather desolate ravine. The forest opens up quite nicely around the falls and in addition to the falls, views out over the valley with Mount Rainier looming in the background are well worth the hike.

![Mask Used in the Black Tamahnous Ceremonies by the Clallams.[The markings are of different colors. The wearer sees through the nostrils.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/599f4601e3df283ad2ee5d10/1603770763763-36565220GMQXRLINDCFB/Mask+Used+in+the+Black+Tamahnous+Ceremonies+by+the+Clallams..jpg)