With COVID, things are still quiet, but I wanted to share a few updates from the Underground, and a few things that we've been up to.

Your Chinook Wawa Word of the Day: Sitkum

SITKUM

[SIT'-kum] — noun, adjective.

Meaning: Half; half of something; part of something; the middle.

Origin: From Chinookan; both inflected (noun) and uninflected (particle) n-shitkum ‘I am half’; a-shitkum ‘she is half’; shítkum '(at the upper) half'; Clatsop asitko,

The word sitkum is used to describe either of two equal or corresponding parts into which something is or can be divided. This is best seen in the term for a "sitkum dolla" (half dollar; fifty cents), though it is also be applied to varying degrees of, or corresponding parts into which something is or can be divided, as seen in "elip sitkum" (more than half) and "tenas sitkum" (less than half; quarter; a small part of something)

Perhaps the largest use of the word sitkum was related to seasons, such as “sitkum kopa waum illahee” (midsummer), and times of the say, as seen in "elip sitkum sun" (forenoon), “sitkum sun” (noon; midday), “kimtah sitkum sun" (afternoon) and “sitkum polaklie" (midnight; half a night). It even appears in the locational descriptor “kah sun mitlite kopa sitkum sun" (south).

The word sitkum also lends it name to Sitkum Glacier, located on the west slopes of Glacier Peak, immediately south of Scimitar Glacier in Washington. Sitkum is also the name of an unincorporated community in Coos County, about 43.5 km (27 miles) north of the hamlet of Remote in the Southern Oregon Coast Range near the East Fork Coquille River.

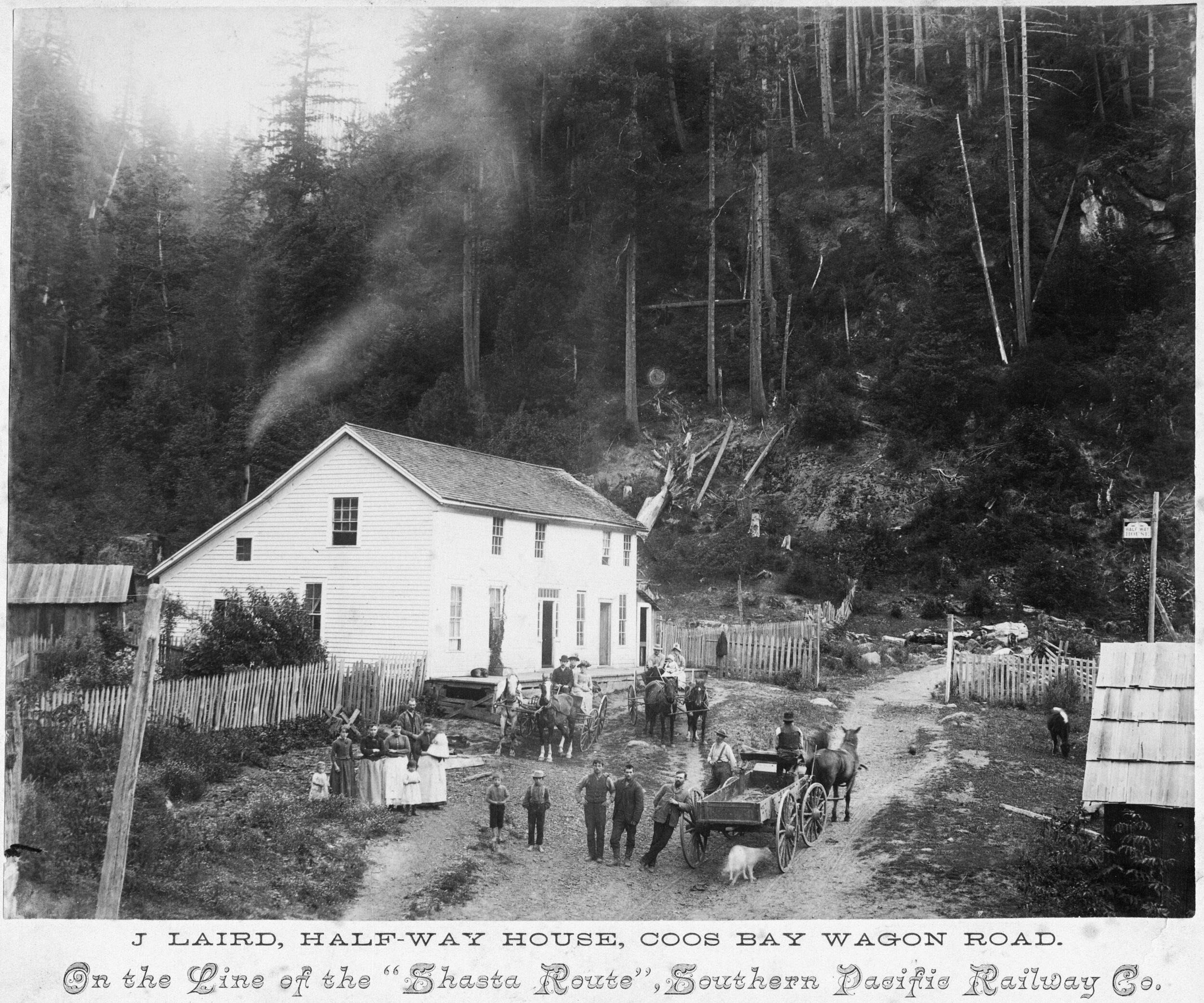

In 1872, John Alva Harry and his wife Chloe (Cook) Harry set up a roadhouse that they called ‘Sitkum’—later known as the Halfway House— as a stagecoach stop near a point halfway between Roseburg and Coos City on the Coos Bay Wagon Road. The establishment was a combination restaurant, tavern, rooming house, and telegraph station where travelers could stop to eat while horses were changed or spend the night.

James Laird Halfway House in Sitkum, Oregon

In the following years the small citizenry of Sitkum would also build a post office and grade school.

Sitkum Post Office

James, Daniel, and Nancy Belle (Harry) Laird property. Sitkum Post Office located in Laird house.

In 1915, the mail stages switched to a less steep road along the Middle Fork of the Coquille River. This route was favored by more and more traffic, and eventually there was little need for travelers’ accommodations in Sitkum. Even so, the Halfway House at Sitkum would stay in operation until 1964.

Today there is little left of the community, and the Sitkum School was converted into a residence, though the former teacher's house and the gym still exist on the grounds.

Your Chinook Wawa Word of the Day: Klonas

KLONAS

[klo'-NASS] — adverb.

Meaning: Perhaps; probably; doubtful; might; may; maybe so; I do not know; who knows

Origin: Chinook tlunas ‘maybe,’ ‘don’t know’

Klonas (sometimes spelled as klonass) is a word used as an expression of indecision, uncertainty, or doubt in the mind of the speaker, and in many ways equivalent to the Spanish term quién sabe, “who knows?”.

A conditional or suppositive meaning is given to a sentence by the word ‘klonas’, though it should be noted that ‘klonas’ is used differently from ‘spose’ (suppose; if), something which is sometimes confused by novice learners of Chinook Wawa.

An unknown person would simply be identified as “klonas klaksta” (somebody), while finding your hotel room requires looking for a specific “klonas kunsih” (number).

If someone were to ask you if it was going to rain today, you could respond “klonas halo” (probably not) or "klonas nowitka" ( probably so, perhaps so; maybe). If both of something could equally apply to a situation, one could simply say “klonas klonas” (either-or).

Examples:

“Kah mika kahpho?” (Where is your brother?)

“Klonas.” (I don't know; who knows?)

"Klonas yaka chako tomollo." (Perhaps he will come tomorrow)

“Klonas nika klatawa.” (Perhaps I shall go; maybe I’ll go)

SLAHAL

GAMES OF THE FIRST NATIONS: SLAHAL

Slahal or Lahal (with slight spelling and pronunciation variations including Sla-hal, Slhahal, Lahall, and Lahalle), is a gambling game of the indigenous peoples of Cascadia, especially along the Salish Sea, which combines song, sacred ritual, intense competition and guesswork.

Known by titles such as ‘the bone game’ (from the playing pieces), ‘the stick game’ (from the scoring pieces), ‘hand game’, ‘gambling game’, or ‘bloodless war game’, it also has regionally specific names in different languages and dialects; in the area around the Burrard Inlet of British Columbia it is often called Slahal or Slhahal, as well as Sk’ak’eltx among the Squamish, while in the north of Vancouver Island, it is called A'la'xwa (sometimes rendered as Lahal) by the Kwakwaka'wakw, and in the eastern Chilcotin Plateau and the Cariboo Plateau it is known as Sllekméw'es among the Secwepemc people.

HISTORY

Oral histories of the First Nations hold that Slahal is an ancient game, played since time immemorial. Among the Coast Salish oral tradition, The Creator gave ‘the stick game’ to humanity at the beginning of time as a way to settle disputes and serve as an alternative to war.

Another story holds that at the beginning of time humans and animals were in direct competition for dwindling food. The Creator gave humans and animals a game to play — Slahal — and decreed that whoever won the game could eat the other from then on. The two sides played against each other, but humans were gradually losing, down to their last stick, they beseeched the Creator to take pity on them. So the Great Spirit let humans win the game, but under the condition that they follow four laws — to turn away from greed, lust, hate, and jealousy. In doing so, the Great Spirit gave the people a gift, to show them who they were, and from then on people have used the game to settle disputes through “bloodless war.”

Physical evidence indicates that the game dates to before the end of the last Ice Age, with a set of 14,000-year-old bone playing pieces, the oldest found yet, discovered along with other cultural artifacts in Douglas County in the late 1980’s. Today these pieces reside with the Washington State Historical Society Museum in Tacoma.

The game serves multiple roles in culture of the First Nations, being a form of entertainment, a means of economic gain through gambling, and serving as a common way to engage with others in the community and with peoples across territorial boundaries in the exchange of goods, information and even lands and people. In addition to conflict resolution between groups, Slahal also played at many occasions, celebrations, and gatherings, serving as a way of healing and bringing people together.

In historic times, prizes played for could be valuables such as clothing, blankets, shawls, horses, buckskin, and trade items, though today prizes can be anything that is of special value, ranging from traditional craft items to money, televisions, game consoles, and many modern accouterments.

The rules and methods of how to play have changed throughout the years, and have some regional variation. Due to the historic suppression of cultural ways, the game was almost lost, though today it has been restored to cultural prominence thanks to the work of anthropologists working with elders of the First Nations. The rules listed below are an approximation based on multiple sources.

RULES

The game is played with two opposing teams of five or six players each, though there can be more if desired, so long as the teams are of equal size. Some sources say that the game always starts with an open traditional game where the men play against the women.

There are two pairs of ‘bones’ used in the game. Traditionally these were cut and polished shin bones from the foreleg of a deer or other animal, though wood or antler are not uncommon material substitutes. Regardless of what the pieces are made of, they must be small enough to hide in one’s hand, and are not noticeably different except in colour, with one pair (sometimes referred to as ‘white’ or ‘female’) being plain and unmarked, and the other pair (sometimes referred as ‘black’ or ‘male’) being carved or marked in some way with a black stripe or similar pattern, usually along the middle of the piece. Some teams travel with their own ‘bones’, which they believe are lucky, not unlike modern tabletop gamers who might own a set of ‘lucky’ dice.

The game also uses an equal number of ‘Tally Sticks’ (sometimes called Guessing Sticks), typically between six and fourteen, depending on traditions and rules, with ten or twelve being the most common, which are used for keeping score, and are evenly divided between the teams at the beginning of the game. These are commonly painted or otherwise marked (often half in one set of colors and the other half in another) and/or made of different types of wood.

Additionally there is a ‘King Stick’ or ‘Kick Stick’ (sometimes referred to as the ‘King Pin’), which is an extra stick, usually longer and specially marked (sometimes painted both colors, one color at each end) which is initially played for by each team’s elected leader, who are typically referred to as ‘doctors’. This initial contest, analogous to a coin toss in many sports, can either be through one ‘doctor’ holding a set of the ‘bones’ (one marked and one unmarked) and the opposing team’s ‘doctor’ guessing which hand the marked ‘bone’ is in, or decided via a simple rock-paper-scissors style decision. The winner (in this example referred to as ‘Team A’) is awarded the ‘King Stick’ and starts the game with control of the ‘bones’.

The game begins with each team dividing the ‘Tally Sticks’ evenly between them. Team A and Team B arrange themselves in two straight line formations where players sit on the ground or on benches, each team facing the other with their set of ‘Tally Sticks’ laid out in front of them. Each round a team’s ‘doctor’ will decide which two players (seated next to each other) will hold the ‘bones’ when they are in possession, and which team member will be the ‘shooter’ when it is their turn to guess the location of the unmarked ‘bones’.

On Team A, the two players selected by the ‘doctor’ take two bones each, one marked and one unmarked, and conceal them in their hands. The ‘doctor’ of Team A then begins a song, accompanied by drums (in the past drums were rarely used, with rattles, horns, and a longboard and sticks) as well as the pounding of sticks by the other members of the team to keep a beat, while the two players have a minute or so to secretly swap the bones back and forth between their hands and each other (either behind their back or under a scarf) in rhythm with the music, while the ‘shooter’ of Team B tries to observe and track the position of the two unmarked bones. The musical accompaniment is sometimes used to taunt and distract the opposing team, and is also often combined with occasional yells or random body gestures meant to disrupt the concentration of Team B’s ‘shooter’.

After the elapsed time, or when signaled by the ‘doctor’ of Team B that they are ready to guess, the players of Team A then hold their closed hands out in front of them, presenting them to the designated ‘shooter’ of Team B.

At this point, Team B’s ‘shooter’ must guess (or suss out) the location of the two unmarked ‘bones’ based on one of four possible permutations:

The ‘shooter’ on Team B then makes their guess as to where the location of the unmarked ‘bones’ are hiding by pointing with one hand.

HAND GESTURES

Pointing to the shooter’s right indicates they think both UNMARKED ‘bones’ are in the left hands.

Pointing to the shooter’s left indicates they think both UNMARKED ‘bones’ are in the right hands.

Pointing downward indicates they think both UNMARKED ‘bones’ are in the “inside” hands.

Pointing upward indicates they think both UNMARKED ‘bones’ are in the “outside” hands.

Often the ‘shooter’ will make a ‘fake shot’ by moving their hands quickly, either turning back the finger or not making the complete gesture. This is done in an effort to get into the opposing player’s head by tricking those over-eager to show the wrong selection into revealing the position of the unmarked ‘bone’.

If the ‘shooter’ of Team B does not manage to guess the location of either of the two unmarked bones, their team must surrender two tally sticks to Team A, who will then continue the game by hiding the ‘bones’ once again.

If the shooter of Team B manages to guess the location of only ONE UNMARKED ‘bone’, their team must surrender one of the Tally Sticks to Team A, who will then continue the game by hide the ‘bones’ once again and Team B will have another chance to guess which hand the remaining UNMARKED ‘bone’ is.

If the shooter of Team B guesses the location of BOTH UNMARKED ‘bones’, then their team wins control of the ‘bones’ and it is now Team A’s turn to guess.

The game continues back and forth in this manner until one team has won all of the ‘Tally Sticks’ from the other team, with the ‘King Stick’ being the last surrendered.

The additional rules are fairly simple:

Players can only play for one team, and may not switch teams until the end of the game, though in important competitions a player must stay with their own team.

When a player is ready to show the ‘bones’, they must show them as they are, and cannot change their position, otherwise the ‘bone’ are forfeited to control of the opposing team.

A game can also be forfeited in the event of an opposing team member holding two bones in one hand when the ‘shooter’ points.

OTHER NOTES

It is customary that during play, spectators will often place bets on teams, or individual matches within the game between one ‘shooter’ and the other team's ‘bone’ hiders.

While there is no official time limit for games, average matches typically last roughly an hour and a half, though some games played for high stakes could last for several hours, or even days, with the “Tally Sticks’ passing from one side to the other many times as one team nearly wins, then loses their sticks again to the other side, and back again, before the ‘King Stick’ is finally won. In these serious high stakes games, in which the teams often play for pots of thousands of dollars, a judge will be appointed to keep the contest fair.

PLAYING AT HOME OR ON THE ROAD

For those wishing to play an impromptu game, or if they lack proper equipment, the ‘Tally Sticks’ can be substituted with pens or pencils, and the ‘bones’ can be substituted with large rubber erasers.

If there are only two players available, then the rules can be simplified, with fewer ‘Tally Sticks’, only one pair of ‘bones’ used, and the guess limited to right or left.

Your Chinook Wawa Word of the Day: Kull

KULL

[kul] — adjective.

Meaning: Hard (in substance); solid; hard to do; tough; difficult.

Origin: From a Chinookan particle q’ul ‘strong’; q’ul-q’ul ‘strong’, ‘hard’, ‘too difficult’.

A word used to describe making something “hyas kull” (tight; fast), or changing the state of something such as "mamook kull" (to harden; to cause to harden) and "chako kull" (to become hard), as seen in “kull snass" (ice) and “kull tatoosh" (cheese) describing the solidifying state of rain and milk, respectively. Conversely, the expressions ”halo kull” (easy; not difficult) and “wake kull” (soft; tender) could also be used as alternative ways to describe something that is ‘soft’ or ‘not hard’.

It is occasionally seen in expressions like “hyas kull spose mamook” (it is very hard to do so), or describing a substance, like the “kull stick” (oak), which could be used as a byword for any sort of hardwood in Cascadia.

2021 U.S. Census Redistricting: Exploring Watershed Based Voting Districts

Every 10 years, the United States completely erases current voting district borders, and creates new ones using census data that has tracked demographic changes over the past ten years.

How these districts are drawn is incredibly important, and in many states, is used as a tool of disenfranchisement, racism, and reinforcing voter disparities. Ensuring a fair voter redistricting process is one of the most important ways to ensure equity, transparency and accountability in our democratic institutions. This process is currently underway, and voting commissions are being formed to explore the best way to redraw these districts.

We've launched a Cascadia Discord Server!

Your Chinook Wawa Word of the Day: Lemooto

LEMOOTO

[le-MOO'-to] or [lam'-MU-to] — noun.

Meaning: Sheep; mutton.

Origin: French, les moutons, “sheep”

Sometimes spelled as lemoto or limoto, it refers to sheep, and naturally all things related to them, such as “man lemooto” (ram), "klootchman lemooto" (ewe), “tenas lemooto” (lamb), and "lemooto house" (fold, sheepfold). The word was also used for “mutton”, though if one wanted to specify, they could say “lemooto itlwillie” or “lemooto yaka itlwillie".

The English word “sheep” was also used from time to time, such as in “hiyu sheep” (flock), “sheep yaka tupso lemooto yakso” (wool), and the heavily English “sheep yaka meat” (mutton)

The Sound of the Yurok language (Numbers, Sentences & Phrases)

Yurok (also Chillula, Mita, Pekwan, Rikwa, Sugon, Weitspek, and Weitspekan) is an Algic language. It is the traditional language of the Yurok of Del Norte County and Humboldt County on the northwest coast of California. The name Yurok comes from the Karuk ‘yuruk’, literally meaning 'downriver'. The Yurok traditional name for themselves is Puliklah, from ‘pulik’ (‘downstream') + -’la’ ('people of'), thus equivalent in meaning to the Karuk name by which they came to be known in English.

Yurok is distantly related to its neighbor Wiyot, and to languages belonging to the Algonquian language family spoken across central and eastern North America, including Blackfoot, Cree, Ojibwe, and many others. Linguists believe that Wiyot, Yurok, and all the Algonquian languages descend from a single common ancestor spoken thousands of years ago, perhaps somewhere in present-day eastern Washington or Oregon or northern Idaho. The relations and history of these languages are areas of active research among linguists, archaeologists, and historians.

Yurok nouns and verbs are assembled and change their forms in patterns that are sometimes elaborate, expressing a variety of meanings. Unlike English, where most nouns change their form to make them plural (cat vs. cats, for example, or man vs. men), Yurok nouns usually do not change their form: puesee can mean "cat" or "cats", and 'yoch can mean "boat" or "boats". However, a very few nouns do change their form:

mewah mewahsegoh perey pegerey wer'yers wer'yernerk huuek huueksoh

“Boy” “Boys” “Old Woman” “Old Women “Girl” “Girls” “Child” “Children”

However, unlike English, Yurok nouns do sometimes change their form to refer to locations:

mech mecheek yoch yoncheek "

“Fire” “in the fire” “boat” “in a boat”

Verbs, meanwhile, can change depending on the subject:

kooychkwok’ kooychkwoh kooychkwoom'

“I buy it.” “we buy it” “you buy it”

"kooychkwoow' kooychkwom’ kooychkwohl

“You (plural) buy it.” “He/She buys it.” “They buy it”

A fascinating aspect of the Yurok language, one that is quite unlike English, is the intricate way that certain meaningful elements combine in the formation of verbs. The table below illustrates typical combinations of elements, used to form verbs with distinct but related meanings. Notice the elements heem- "fast", kwomhl- "back", pkw- "out from an enclosed area", and yohp- "in a circle", to which are added -ech- "go" and -o'rep- "run":

heemechok heemo'repek kwomhlechok kwomhlo'repek

“I hurry” “I run quickly” “I return” I run back”

pkwechok pkwo'repek' yohpechok' yohpo'repek'

“I emerge” “I run out of an enclosed area” “I go in a circle” “I run in a circle”

Yurok sentence patterns are quite different from English patterns; in English, most sentences contain at least a verb (a word like walk, see, know, etc., usually naming an action, experience, situation, etc.) and a subject (indicating who did the action, experienced a situation, etc.): The horse walked, or My teacher sees you, or Your children love pie. But a verb is enough in Yurok, and many Yurok sentences consist of a single word — a verb:

Hlmeyorkwochek' Kwerykweryochem'. 'Sleryhlkerp'erk'

I'm afraid of you.' ‘You are whistling.’ ‘I’m going to blow my nose.’

In English, the basic word order of subject, verb, and object (in sentences that have objects, for example indicating who or what an action was done to) is usually fixed. In Yurok the order of these elements is flexible, depending largely on emphasis and discourse structure. For example, if the context is unambiguous, either of the following sentences might be interchangeable:

Kue pegerk helomey' Helomey' kue pegerk

[article] man to dance - 3sg.infl to dance - 3sg.infl [article] man

The man dances. the man dances.

Compared to English, Yurok word order possibilities are more flexible in sentences like these, but it is not always straightforward to learn the emphasis and discourse patterns that determine which order is used.

One important way Yurok and English sentence patterns differ is that Yurok has a large class of preverbs: short words, typically, that express relative time, location, negation, and relations between events, among many other meanings. As the name suggests, preverbs occur before the verb in a sentence. In the following sentences, for example, the preverb keech means something recently started happening and is still happening, the preverb kee means something will happen in the future, and the preverb combination keech + ho means something has already happened (and is still true).

Keech keepuen Kee kochpoksek' Kues keech ho neskwechoom'? Kues keech ho neskwechoom'?'

“It’s winter (now)” “I will think it over.” “I will think it over.” “When did you arive?”

Preverbs are used in almost every Yurok sentence, and it is common for two, three, or even more to be combined in a sentence. The idiomatic use of preverb combinations is an indication of real fluency in the language.

Decline of the language began during the California Gold Rush, due to the influx of new settlers and the diseases they brought with them. Native American boarding schools initiated by the United States government with the intent of incorporating the native populations of America into mainstream American society increased the rate of decline of the language. The language was officially declared extinct with the death of Archie Thompson, the last native speaker, on March 26, 2013

However, a language revival program The program to revive Yurok has been lauded as the most successful language revitalization program in California. As of 2014, there are six schools in Northern California that teach Yurok - 4 high schools and 2 elementary schools.

The last known native speaker, Archie Thompson, was the last of 20 elders who helped revitalize the language over the last few decades, after academics in the 1990s predicted it would be extinct by 2010. He made recordings of the language that were archived by UC Berkeley linguists and the tribe, spent hours helping to teach Yurok in community and school classrooms, and welcomed apprentice speakers to probe his knowledge." Linguists at UC Berkeley began the Yurok Language Project in 2001. Professor Andrew Garrett and Dr. Juliette Blevins collaborated with tribal elders on a Yurok dictionary that has been hailed as a national model. The Yurok Language Project has gone much more in depth than just a printed lexicon, however. The dictionary is available online and fully searchable. It is also possible to search an audio dictionary - a repository of audio clips of words and short phrases.

As of February 2013, there were over 300 basic Yurok speakers, 60 with intermediate skills, 37 who are advanced, and 17 who are considered conversationally fluent. As of 2014, nine people were certified to teach Yurok in schools. Since Yurok, like many other Native American languages, uses a master-apprentice system to train up speakers in the language, having even nine certified teachers would not be possible without a piece of legislation passed in 2009 in the state of California that allows indigenous tribes the power to appoint their own language teachers.

Other resources with more detailed information include R. H. Robins's book The Yurok language: Texts, grammar, lexicon (1958) and a Yurok Language Project booklet Basic Yurok grammar (2010), which can be download here.

The Sound of the Salish Language (Numbers, Greetings, Phrases & Story)

The Salish or Séliš language, also known as Kalispel–Pend d'oreille, Kalispel–Spokane–Flathead, or, to distinguish it from the Salish language family to which it gave its name, Montana Salish, is a Salishan language with dialects spoken (as of 2005) by about 64 elders of the Flathead Nation in north central Montana and of the Kalispel (Qalispé) in northeastern Washington, and by another 50 elders (as of 2000) of the Spokane (Npoqínišcn) of Washington.

As with many other languages of northern North America, Salish is polysynthetic; like other languages of the Mosan language area, there is no clear distinction between nouns and verbs. Salish is famous for native translations that treat all lexical Salish words as verbs or clauses in English—for instance, translating a two-word Salish clause that would appear to mean "I-killed a-deer" into English as I killed it. It was a deer.

As of 2012, Salish is "critically endangered" in Montana and Idaho according to UNESCO, with all native speakers being elderly. However efforts are being made to revive it: it is taught and used as a language of instruction at a number of regional schools, like the Nkwusm Salish Immersion School, in Arlee, Montana.

Public schools in Kalispell, Montana offer language classes, a language nest, and intensive training for adults. An online Salish Language Tutor and online Kalispel Salish curriculum are available. A dictionary, "Seliš nyoʔnuntn: Medicine for the Salish Language," was expanded from 186 to 816 pages in 2009; children's books and language CDs are also available.

The Salish Kootenai College, offers Salish language courses, and trains Salish language teachers at its Native American Language Teacher Training Institute as a part of its ongoing efforts to preserve the language, and the college even broadcasts programs in Salish on the Salish Kootenai College TV station. As of May 2013, the organization Yoyoot Skʷkʷimlt ("Strong Young People") is teaching language classes in high schools.

Salish-language Christmas carols are popular for children's holiday programs, which have been broadcast over the Salish Kootenai College television station, and Salish-language karaoke has become popular at the annual Celebrating Salish Conference, held in Spokane, Washington. As of 2013, many signs on U.S. Route 93 in the Flathead Indian Reservation include the historic Salish and Kutenai names for towns, rivers, and streams. The Missoula City Council is seeking input from the Salish-Pend d'Oreille Culture Committee regarding appropriate Salish-language signage for the City of Missoula.

The Sound of the Tlingit language (Numbers, Greetings, Phrases & Story)

The Tlingit language is spoken by the Tlingit people in Southeast Alaska from Yakutat (Yaakwdáat, Yàkwdât) south to Portland Canal, and from British Columbia into south-central Yukon Territory between Tagish and Kaska northward. The Tlingit language is distantly related to Eyak and the Athabaskan languages as a branch of the Na-Dene language family, and is part of the larger Dené–Yeniseian language family. Although the name is spelled “Tlingit” in English it is actually pronounced closer to “Klinkit”. This is due to the spelling and the pronunciation in English having two different approximations of the voiceless lateral fricative [ɬ] spelled as either ł or l in Tlingit.

The history of Tlingit is poorly known, mostly because there is no written record until the first contact with Europeans around the 1790s. Documentation was sparse and irregular until the early 20th century. The language appears to have spread northward from the Ketchikan–Saxman area towards the Chilkat region since certain conservative features are reduced gradually from south to north. The shared features between the Eyak language, found around the Copper River delta, and Tongass Tlingit, near the Portland Canal, are all the more striking for the distances that separate them, both geographic and linguistic.

Tlingit word order is SOV when non-pronominal agent and object phrases both exist in the sentence. However, there is a strong urge to restrict the argument of the verb phrase to a single non-pronominal noun phrase, with any other phrases being extraposed from the verb phrase. If a noun phrase occurs outside of the verb phrase then it is typically represented in the verb phrase by an appropriate pronoun.

Despite not being a fusional language, Tlingit is still highly synthetic as an agglutinating language, and is even polysynthetic to some extent. The verb, as with all the Na-Dené languages, is characteristically incorporating. Nouns are in comparison relatively simple, with many being derived from verbs.

Extensive effort is being put into revitalization programs in Southeast Alaska to revive and preserve the Tlingit language and culture.

The Sound of the Nootka / Nuu-chah-nulth language (Numbers, Sentences, Phrases & Story)

Nuu-chah-nulth, also known as Nootka, is Wakashan language historically spoken on the west coast of Vancouver Island, from Barkley Sound to Quatsino Sound in British Columbia by the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples. Nuu-chah-nulth is a Southern Wakashan language related to Nitinaht and Makah.

It is the first language of the indigenous peoples of the Cascadian Coast to have documentary written materials describing it. In the 1780s, Captains Vancouver, Quadra, and other European explorers and traders frequented Nootka Sound and the other Nuu-chah-nulth communities, making reports of their voyages. From 1803–1805 John R. Jewitt, an English blacksmith, was held captive by chief Maquinna at Nootka Sound. He made an effort to learn the language, and in 1815 published a memoir with a brief glossary of its terms.

The Nuu-chah-nulth language contributed much of the vocabulary of the Chinook Jargon. It is thought that oceanic commerce and exchanges between the Nuu-chah-nulth and other Southern Wakashan speakers with the Chinookan-speaking peoples of the lower Columbia River led to the foundations of the trade jargon that became known as Chinook. Nootkan words in Chinook Jargon include hiyu ("many"), from Nuu-chah-nulth for "ten", siah ("far"), from the Nuu-chah-nulth for "sky".

A dictionary of the language, with some 7,500 entries, was created after 15 years of research. It is based on both work with current speakers and notes from linguist Edward Sapir, taken almost a century ago. The dictionary, however, is a subject of controversy, with a number of Nuu-chah-nulth elders questioning the author's right to disclose their language.

The provenance of the term "Nuu-chah-nulth", meaning "along the outside [of Vancouver Island]" dates from the 1970s, when the various groups of speakers of this language joined together, disliking the term "Nootka" (which means "go around" and was mistakenly understood to be the name of a place, which was actually called Yuquot). The name given by earlier sources for this language is Tahkaht; that name was used also to refer to themselves (the root aht means "people").

Translations of place names

Nuuchahnulth had a name for each place within their traditional territory. These are just a few still used to this day:

hisaawista (esowista) – Captured by clubbing the people who lived there to death, Esowista Peninsula and Esowista Indian Reserve No. 3.

Yuquot (Friendly Cove) – Where they get the north winds, Yuquot

nootk-sitl (Nootka) – Go around.

maaqtusiis – A place across the island, Marktosis

kakawis – Fronted by a rock that looks like a container.

kitsuksis – Log across mouth of creek

opitsaht – Island that the moon lands on, Opitsaht

pacheena – Foamy.

tsu-ma-uss (somass) – Washing, Somass River

tsahaheh – To go up.

hitac`u (itatsoo) – Ucluelet Reserve.

t’iipis – Polly’s Point.

Tsaxana – A place close to the river.

Cheewat – Pulling tide.

The Sound of the Haida language (Numbers, Greetings, Sentences & Phrases)

Haida (X̱aat Kíl, X̱aadas Kíl, X̱aayda Kil, Xaad kil) is the language of the Haida people, spoken in the Haida Gwaii archipelago off the coast of British Columbia and on Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. An endangered language, Haida currently has 24 native speakers, though revitalization efforts are underway.

At the time of the European arrival at Haida Gwaii in 1774, it is estimated that Haida speakers numbered about 15,000. Epidemics soon led to a drastic reduction in the Haida population, which became limited to three villages: Masset, Skidegate, and Hydaburg. Positive attitudes towards assimilation combined with the ban on speaking Haida in residential schools led to a sharp decline in the use of the Haida language among the Haida people, and today almost all ethnic Haida use English to communicate.

Classification of the Haida language is a matter of controversy, with some linguists placing it in the Na-Dené language family and others arguing that it is a language isolate. Haida itself is split between Northern and Southern dialects, which differ primarily in phonology. The Northern Haida dialects have developed pharyngeal consonants, typologically uncommon sounds which are also found in some of the nearby Salishan and Wakashan languages.

The Haida sound system includes ejective consonants, glottalized sonorants, contrastive vowel length, and phonemic tone. The nature of tone differs between the dialects, and in Alaskan Haida it is primarily a pitch accent system. Syllabic laterals appear in all dialects of Haida, but are only phonemic in Skidegate Haida. Extra vowels which are not present in Haida words occur in nonsense words in Haida songs. There are a number of systems for writing Haida using the Latin alphabet, each of which represents the sounds of Haida differently.

While Haida has nouns and verbs, it does not have adjectives and has few true adpositions. English adjectives translate into verbs in Haida, for example 'láa "(to be) good", and English prepositional phrases are usually expressed with Haida "relational nouns", for instance Alaskan Haida dítkw 'side facing away from the beach, towards the woods'. Haida verbs are marked for tense, aspect, mood, and evidentiality, and person is marked by pronouns that are cliticized to the verb. Haida also has hundreds of classifiers. Haida has the rare direct-inverse word order type, where both SOV and OSV words orders occur depending on the "potency" of the subject and object of the verb. Haida also has obligatory possession, where certain types of nouns cannot stand alone and require a possessor.

Today most Haidas do not speak the Haida language. The language is listed as "critically endangered" in UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, with nearly all speakers elderly. As of 2003, most speakers of Haida are between 70 and 80 years of age, though they speak a "considerably simplified" form of Haida, and comprehension of the language is mostly limited to persons above the age of 50. The language is rarely used even among the remaining speakers and comprehenders.

The Haida have a renewed interest in their traditional culture, and are now funding Haida language programs in schools in the three Haida communities, though these have been ineffectual. Haida classes are available in many Haida communities and can be taken at the University of Alaska Southeast in Juneau, Ketchikan, and Hydaburg. A Skidegate Haida language app is available for iPhone, based on a "bilingual dictionary and phrase collection comprised of words and phrases archived at the online Aboriginal language database FirstVoices.com."

In 2017 Kingulliit Productions began filming on SGaawaay K’uuna ("Edge of the Knife"), the first feature film to be acted entirely in dialects of the Haida language.

Your Chinook Wawa Word of the Day: Tzum

TZUM

[tsŭm] or [chŭm] — adjective, noun.

Meaning: Color; spot; spotted; stripe; writing; write; written; mark; marked; figures; colors; printing; pictures; paint; painted; ornamental colors; tint; mixed colors; festive colors.

Origin: From a Chinookan particle ts’am 'variegated (in color)', ts’em 'spotted' > Lower Chinook ch'əám, “variegated”

Sometimes spelled as ‘chum’, the word is most famously applied to the Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), found from southern California to Alaska and off the coasts of Japan and Korea, while the term "tzum sammon" is used to refer to the steelhead and any number of spotted trout in the region.

The extremely versatile expression "mamook tzum" can mean anything from ‘to write’, ‘to mark’, ‘to draw’, ‘to paint’, ‘to print’, ‘dye’, ‘copy’, ‘engrave’, and ‘subscribe’.

Someone like a “tzum man” (writer; penman; clerk) would likely use a "tzum stick" (pencil; pen; paintbrush) and "klale chuck kopa mamook tzum" (ink) to create “tzum pepah” (picture; writing; a letter; printed material) or denote "tzum illahee" (surveyed land).

Likewise, a woodsman will “tzum kah” (track) or "tzum kah lepee mitlite" (mark where the foot was) while they, “mamook tzum illahee” (survey) or “mamook tzum iktas” (assess) the area to “mamook kunsih” (enumerate) items in it.

While this word also applies to a “tzum seeowist” (photograph; postage stamp), “tzum pasese” (quilt; bed quilt), or “tzum sail” (calico; printed cloth), it could just as easily have to do with colored stones or availability of ochre or other pigments.

The Sound of the Chinook Jargon language (Numbers, Greetings & Story)

Chinook Wawa (also known as Chinuk Wawa or Chinook Jargon, and sometimes Chinook Lelang) is a nearly extinct pidgin trade language that bordered on being a creole language which served as a true lingua franca of the Cascadia bioregion for several hundred years.

Partly related to, but not the same as, the aboriginal language of the Chinook people, Chinook Wawa actually has its roots in earlier regional trade languages, like Haida Jargon or Nookta Jargon, which itself was a simplified version of Nuu-chah-nulth combined with words and elements of the different Wakashan, Salishan, Athapaskan, and Penutian languages. With the arrival of European explorers, trappers, and traders, many new words were added from French and English, with modifications made in pronunciation, using only those sounds that could be pronounced with ease by all speakers. Grammatical forms were reduced to their simplest expression, and variations in mood and tense conveyed only by adverbs or by the context. With a relatively small lexicon of only a few hundred words, it is not only easy to learn but possible to say almost anything with a little patience and poetic imagination.

During the fur trade in the early 19th century, Chinook Wawa had more than 100,000 speakers, spreading from the lower Columbia River, first to other areas in modern Oregon and Washington, then British Columbia, and as far as Alaska and the Yukon Territory. It was used as a common trade language between the hundreds of indigenous tribes and nations from the region and was incorporated by early English, French, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, and other immigrants, pioneers, and traders who made the area their home, and naturally became the first language in multi-racial households and in multi-ethnic work environments such as canneries, lumberyards, and ranches where it remained the language of the workplace well into the middle of the 20th century.

HOW IS IT PRONOUNCED?

As a trade language, Chinook Wawa is by its very nature meant to be usable by people from many different linguistic backgrounds, so naturally, there is no "correct" pronunciation. An individual's pronunciation of a word was necessarily going to be dependent on that person's own language and dialect, be it English, French, Salish, Nuu-chah-nulth, Chinese, or even Hawaiian.

Furthermore, all published lexicons were created by English speakers influenced by standard English spelling methods (and, as everyone knows, there is no consistency at all in English spelling). Still, the wide variation in spellings for many words can give a clue to their potential variation in pronunciation, or for a pronunciation that falls "in-between" the sounds represented (i.e. hiyu / hyiu / hyo is one example, and tikegh / tikke / ticky is another). Though existent in Chinook Jargon, the consonant /r/ is rare, and English and French loan words, such as ‘rice’ and ‘merci’, have changed in their adoption to the Jargon, to ‘lice’ and ‘mahsie’, respectively.

CHINOOK WAWA TODAY.

As a result of deliberate measures of genocide and cultural suppression in the United States and Canada, aboriginal languages, including Chinook Wawa, were suppressed or outright banned, resulting in a decline of speakers. While Chinook Wawa has fallen from use in the late 20th century, it has lived on in many toponyms throughout Cascadia, within many indigenous languages, and in some regional English usage, to the point where most people are unaware that the word or name is originally from Chinook Wawa.

Chinuk Wawa was classified as extinct until the 2000s when it was revived, notably in 2014 with the release of Chinuk Wawa—As Our Elders Teach Us to Speak It by the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, who have since launched the Chinuk Wawa Immersion Language Program. In 2018 a textbook for Chinook Jargon in Esperanto (La Chinuka Interlingvo Per Esperanto,] The Chinook Bridge-Language Using Esperanto) was published by Sequoia Edwards. In 2019 "Chinuk Wawa" became available as a language option on the fanfiction website Archive of Our Own. With a steadily growing interest in Cascadia and its history, Chinook Wawa is seeing a gradual resurgence.

BIOREGIONAL SPOTLIGHT #1: KWONGAN

Want to get involved? Join our next organizers orientation Tuesday, March 2nd at 6pm

Interested in being a part of Cascadia and the Cascadia movement? Join a Cascadia Department of Bioregion organizers meeting where we discuss the basics, talk about how people want to be involved, and then plug people in. No committment needed. Hop on, check it out. Ask questions. See if it’s a good fit.

Share Your Cascadia! Link to Google Form

YOUR CHINOOK WAWA WORD OF THE DAY: PELTON

Investigate West Launches new "Decarbonizing Cascadia" Series

“Getting to Zero: Decarbonizing Cascadia” is a yearlong reporting initiative led by InvestigateWest, in partnership with Grist, Crosscut, The Tyee, the South Seattle Emerald, The Evergrey, and Jefferson Public Radio.